“What marvel that the horns of a monster were betrayed by his sister, when the twisted path was revealed by the gathering of her thread.” Propertius, Elegies 4.4 (trans. Goold)

The earliest literary records of the hero Theseus come from Homer’s Iliad and Odyssey, composed around the 8th century BCE. The legendary founder and king of Athens was, as might be expected, incredibly popular in literature and visual art throughout antiquity. Theseus is born with both divine and royal lineage, granted to him when his mother, Aithra, has intercourse with both the mortal King Aegethus and the god Poseidon on the night of his conception. Like many heroes, he is raised unaware of both his divine and royal lineage, which will only be revealed once he is old enough to return to Attica and claim his status as king. The first of the young hero’s adventures takes place on this homecoming journey, as he must complete six tasks (or labors) before he can safely reach his father’s palace.1 The Six Labors of Theseus, though reminiscent of the trials undertaken by heroes such as Herakles or Jason, read more like an ancient hit-list than a test of mettle or wit.

He travels the coast, enacting vigilante justice upon a series of ancient serial-killers. First he encounters Periphetes, the Club-Bearer; Theseus bashes the man’s head with his own club, before taking it as his new signature weapon. Then Sinis, the Pine-Bender, who kills his victims by tying their limbs to bent trees, which would tear them asunder when released, and gets the same treatment from Theseus. The Crommyonian Sow is next, either a literal wild hog or a crude reference to a female bandit. Either way, she is easily dispatched with a spear. Fourth is Skiron, who kicks travelers over a cliff when they stop to wash his feet; he doesn’t even get the chance to ask Theseus to bend over before he is thrown from the rocks by the hero. Then he comes upon the wrestler Kerkyon, who is no match for the strength of a demigod. Finally, there is Procrustes, the Stretcher. I’m sure you can assume what he did to hapless passers-by. Theseus ends his labors by cutting off his head and feet.2

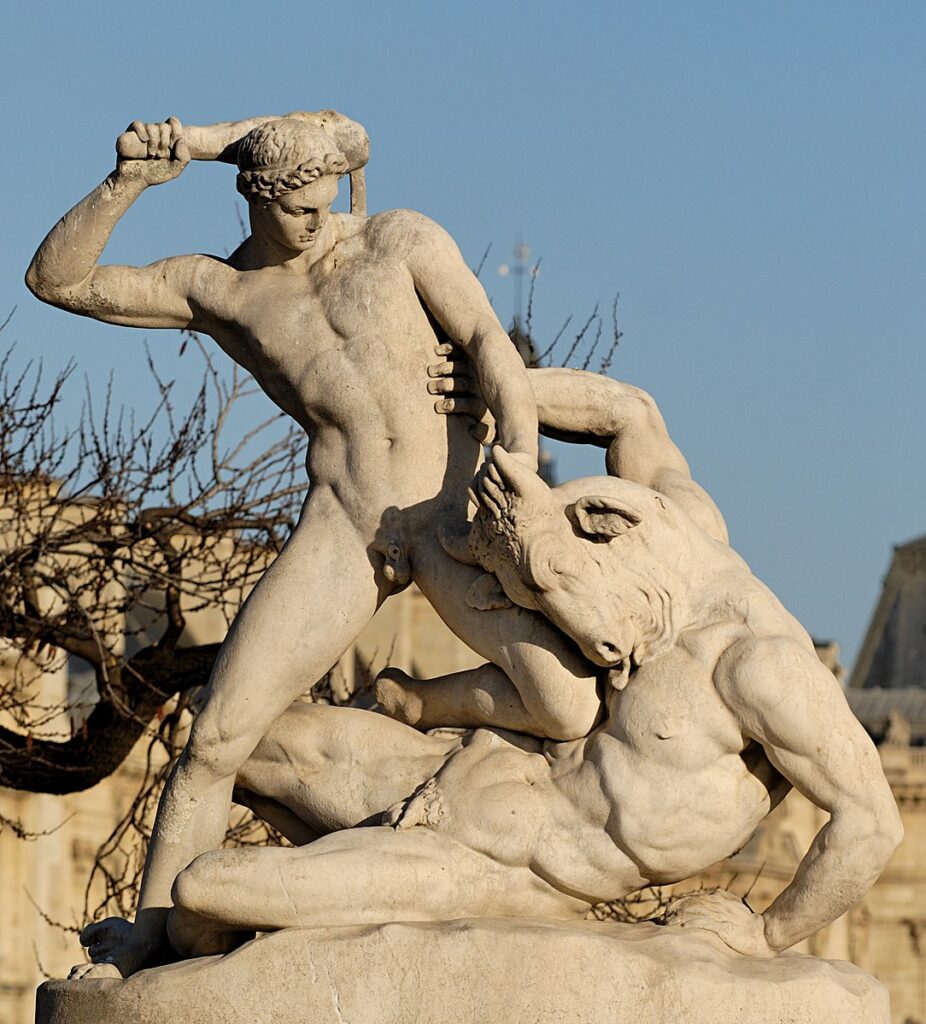

Blood soaked, he returns home to claim his rightful place as King, but is thwarted by his evil stepmother (in some versions, this is Medea, who has fled after the incident with Jason).3 She sets forth even more trials, and his adventures continue. Theseus hunts down and captures the Marathonian bull, the Minotaur’s father, which has escaped captivity to roam wild. He drags the creature back to Athens and finally sacrifices it, as Minos had been unwilling to.4

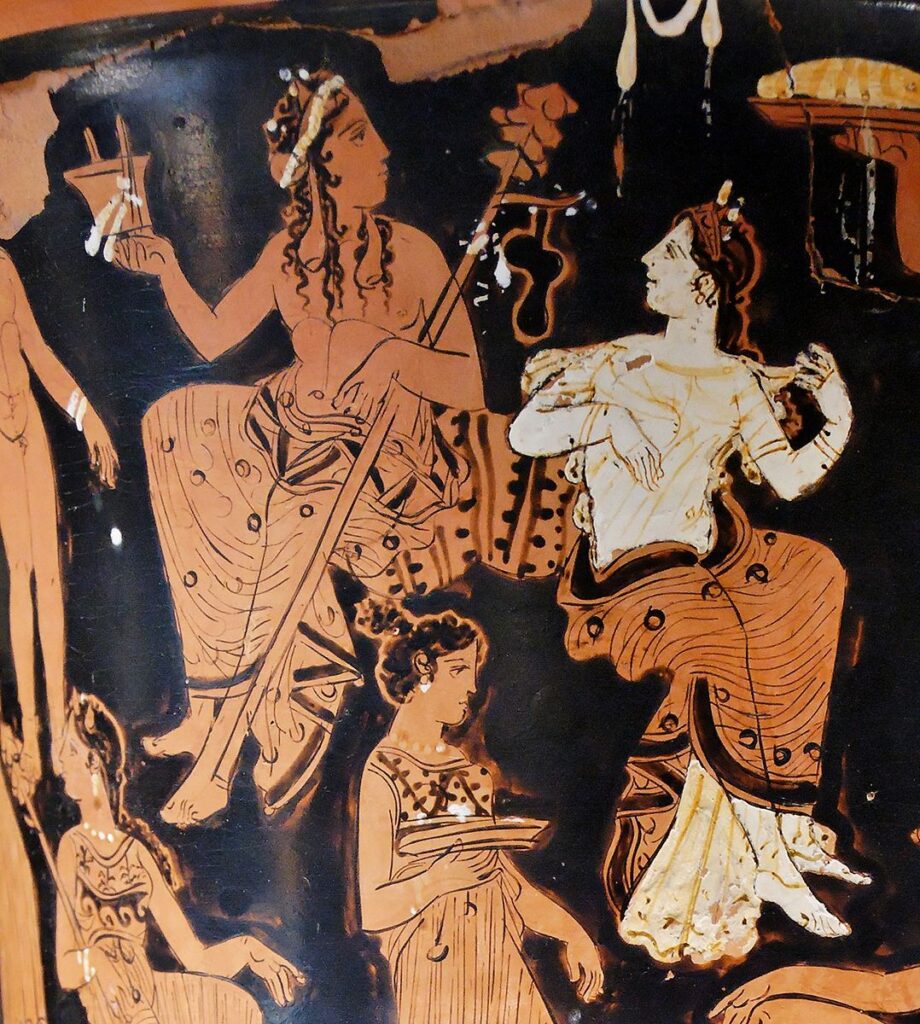

Then, he sets his sights on the Minotaur. He travels to Crete disguised as one of the sacrificial youths. When he arrives at the island, Minos’ daughter Ariadne is instantly infatuated with the strapping young hero. As the Roman poet Catullus writes: “No sooner did she lower him from her incandescent eyes / than she conceived through her body a flame, / and totally, to the center of her bones, she burned.”5

Ariadne betrays her family to aid the hero, providing him with a spool of thread to mark his path through the labyrinth. Not only is this recognized as a betrayal of her father, by siding with the enemy, but also of her brother, in aiding in his killing. Once again, the women of Knossos are led astray by uncontrollable lust. Although, in her defense, it seems few of the Cretan royals are able to resist Theseus’ charms. In some sources, even King Minos himself engages in a sexual relationship with the Athenian hero. The 2nd century CE Greek writer Athenaeus goes as far as to say that: “Minos abandoned his enmity to the Athenians, although it had originated out of the death of his son, out of his love for Theseus.” 6

After Ariadne aids Theseus in slaying the Minotaur, most sources agree that he takes her with him when he leaves Crete, sometimes by force, and the two stop off on the island of Naxos. This is where the sources begin to differ more dramatically on the course of events, though the outcome remains the same. In one of the earliest versions of the story from Hesiod’s Theogony, composed around the 8th century BCE, we’re told that: “Golden-haired Dionysus made blonde-haired Ariadne, the daughter of Minos, his wife: and the son of Cronus made her deathless and unaging for him.”7

While early versions are vague on the details of how exactly Ariadne becomes the bride of Dionysus, later authors expanded the proto-Cinderella story. In some sources, Dionysus is so enthralled by Ariadne’s beauty that he kidnaps her from Theseus, or even forces him to leave her behind.8 In others, such as the one relayed in Apollonius’ 3rd century BCE Argonautica, Theseus abandons Ariadne on the island while she sleeps.9 Dionysus then comes to her rescue, sweeping her off her feet and offering her a far grander life than any mortal husband might have. In Ovid’s Heroides, a collection of fictional letters from mythical women to the men who wronged or betrayed them written around 25 B.C., he imagines Ariadne’s response to Theseus’ abandonment.

Ovid’s Ariadne swings between sorrow, regret, and rage. “Gentler than you have I found every race of wild beasts,” she opens her address. She weeps at the thought of dying alone, and laments that Theseus did not also kill her “with the same bludgeon that slew [her] brother.” She even wishes that she had never helped Theseus kill Asterion, as she no longer has any brothers to come to her rescue.10 Perhaps Asterion could have been a hero himself—saving his sister as Castor and Pollux will save a young Helen when Theseus later kidnaps her—if he had lived to have a chance.11

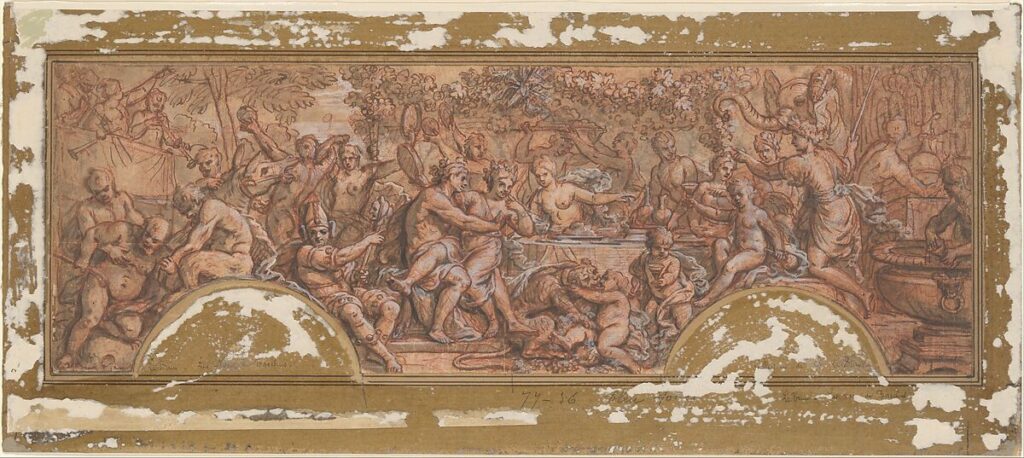

The level of agency Ariadne has in this divine marriage is, unsurprisingly, not something that ancient authors dwelt on. The stories that featured the couple’s married life, however, all seem to imagine their relationship as a perfect match; built upon true mutual affection. In poet and author Ruth Padel’s article “Labyrinth of Desire: Cretan Myth and Us,” she writes that “Pasiphaë’s daughter belongs with this drunk-mad-animal anarchy.”12

Perhaps it is unsurprising that the daughter of the witch-queen, famous for her love of music and dancing, would feel at home in a bacchanal. In one of Ovid’s later works, the Fastī, she appears far from the weeping, betrayed maiden of the Heroides; now joking about Theseus’ abandonment, she wonders: “Why did I sob like a country girl? His lies were my gain.”13

- Greene, Andrew. 2009. “Theseus, Hero of Athens.” In Heilbrunn Timeline of Art History. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. http://www.metmuseum.org/toah/hd/thes/hd_thes.htm ↩︎

- Morris H. Lary, “Theseus: A Legendary Greek Hero”, History Cooperative, June 30, 2022, https://historycooperative.org/theseus/. ↩︎

- “Theseus and His Parents and Stepmother,” Bulletin of the Institute of Classical Studies, Volume 26, January 1979, Pages 18–28, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-5370.1979.tb01043.x

↩︎ - Morris, 2022 ↩︎

- Catullus 64, 91-93 ↩︎

- Athenaeus, Deipnosophistae (trans. Gulick). 3rd century CE. ↩︎

- Hesiod, Theogony, 947 (trans. Evelyn-White). 8th century BCE. ↩︎

- Diodorus Siculus, Library of History 4. 61. 5 (trans. Oldfather). 1st c BCE. ↩︎

- Apollonius Rhodius, Argonautica 3. 997 ff (trans. Rieu). 3rd c BCE. ↩︎

- Ovid, Heroides, Epistle 10 (trans. Showerman). 1st c BCE. ↩︎

- Cartwright, Mark. “Helen of Troy.” World History Encyclopedia. January 27, 2021. https://www.worldhistory.org/Helen_of_Troy/. ↩︎

- Padel, Ruth. “Labyrinth of Desire: Cretan Myth in Us.” Arion: A Journal of Humanities and the Classics 4, no. 2 (1996): 76–87. http://www.jstor.org/stable/20163616. ↩︎

- Ovid, Fasti 3. 459 (trans.Boyle). 1st century CE. ↩︎

Featured Image: Theseus and Minotaur kylix courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This work is in the public domain.

Images:

Theseus and Marathonian Bull krater photograph courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This work is in the public domain.

Theseus and the Minotaur carving at the Archaeological Museum of Delphi, photograph by Zde and licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike 4.0 International license.

Ariadne by Asher Brown Durand, c. 1831 courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This work is in the public domain.

The Wedding Feast of Bacchus and Ariadne by Guy Louis Vernansel the Elder, c. 1709 courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This work is in the public domain.

Bacchus and Ariadne by Giovanni Bastista Tiepolo, c. 1696-1770, courtesy of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. This work is in the public domain.