The Sistine Chapel Ceiling

A Renaissance Icon

by Noelle Weaver

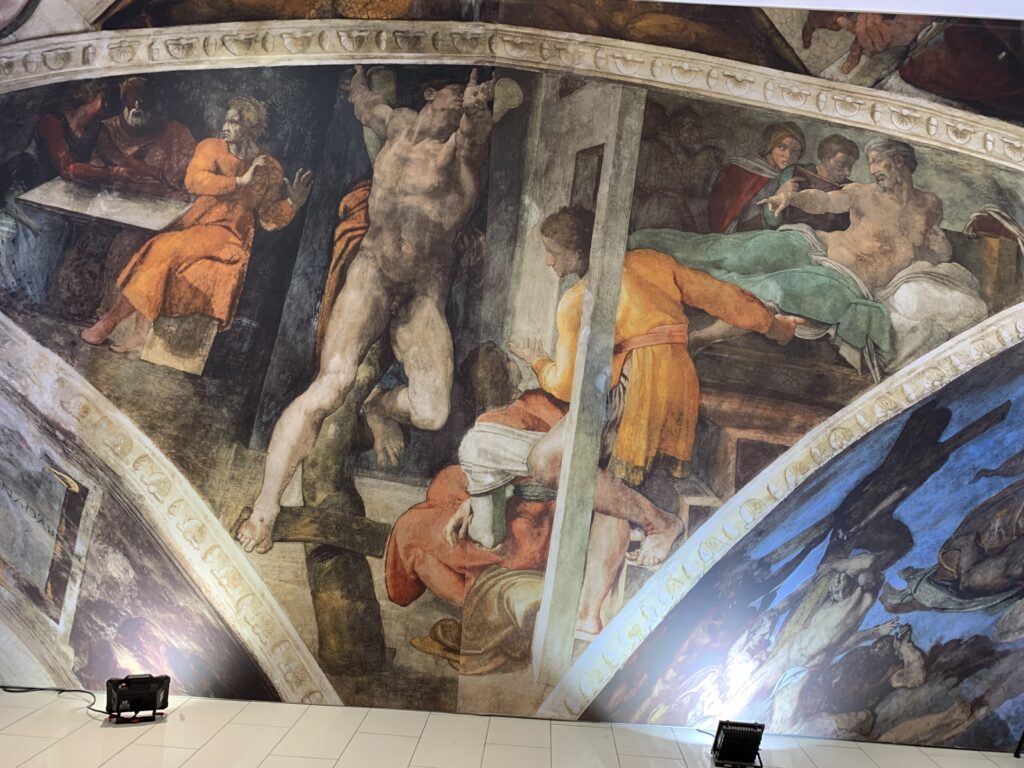

I recently had the opportunity to visit Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel: The Exhibition in Dayton. The art exhibit takes high quality images of the different pieces of the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel in Rome and presents them on canvas for individual to-scale viewing. It gave a unique chance not just to see Michelangelo’s work, but to view it up close and in even more detail than you could get by standing in the Sistine Chapel itself, with the images overhead and far away.

The monumental-quality and complexity of the images becomes even more apparent at this incredible scale. Michelangelo was a sculptor first in his own mind, and while his images don’t have some of the grace and beauty of his contemporaries like Raphael, they’re no less impressive. The works of art may not be the easiest for viewing, but they are a feat of human ingenuity, art, and theology.

The large amounts of nudity in the Sistine Chapel can seem less than sacred, and has been contended and even censored over the centuries. Michelangelo’s own philosophy was that the human form was the highest expression of beauty in nature, because Christian theology holds that people are made in “the image and likeness of God.” With the human body as a fallen but no less divine reflection of the ultimate source of beauty, Michelangelo endeavored to use his imagination to depict the body as close to perfection as possible. This is seen most clearly in The Creation of Adam, and rightly so. Adam is the unfallen and first creation of humankind, and as such he is a physical specimen of bodily perfection. Like the David statue, the physique stretches beyond human limits and reaches for the divine, Platonic perfection.

These are just a few of the images on display in the exhibit, primarily from the major events in Genesis and some from the Old Testament.

Genesis

God in Creation

Separation of Light from Darkness

Creation of the Sun and Moon

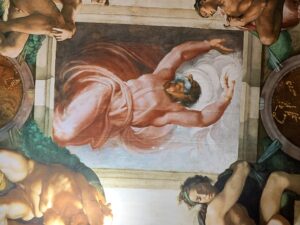

Of course, Michelangelo’s primary source is the Bible, especially Genesis’ accounts. Instead of depicting separate images of Creation step-by-step, instead God is making both the Sun and Moon simultaneously. His gestures indicate his creation, a recurring pose; God is always pointing towards his creation as it springs into existence. We’re even given a time lapse effect, seeing both God forming the planets, and God foreshortened to the left as he makes the plants and vegetation next.

In yet another contrasting angle, God is seen soaring overhead from beneath as he separates the light from the darkness on the first day of Creation in the narrative.

Creation of Man and Woman

One of the most iconic images of Western art is of course the Creation of Adam. It is depicted towards the center of the Sistine Chapel ceiling (although ironically it is the Creation of Eve piece that actually sits in the middle). It is one of Michelangelo’s more visually pleasing works, but no less sculptural or impressive than the rest.

The composition is evocative, and provokes many interpretative questions; why is God surrounded by a billowing cloak rather than free standing like in the earlier Genesis images? Does the cloak just happen to look like the human brain, or is Michelangelo intentionally making the resemblance? Is that Eve at God’s left, implying that she’s already in his plans as his last Creation? This striking image is made to ponder on.

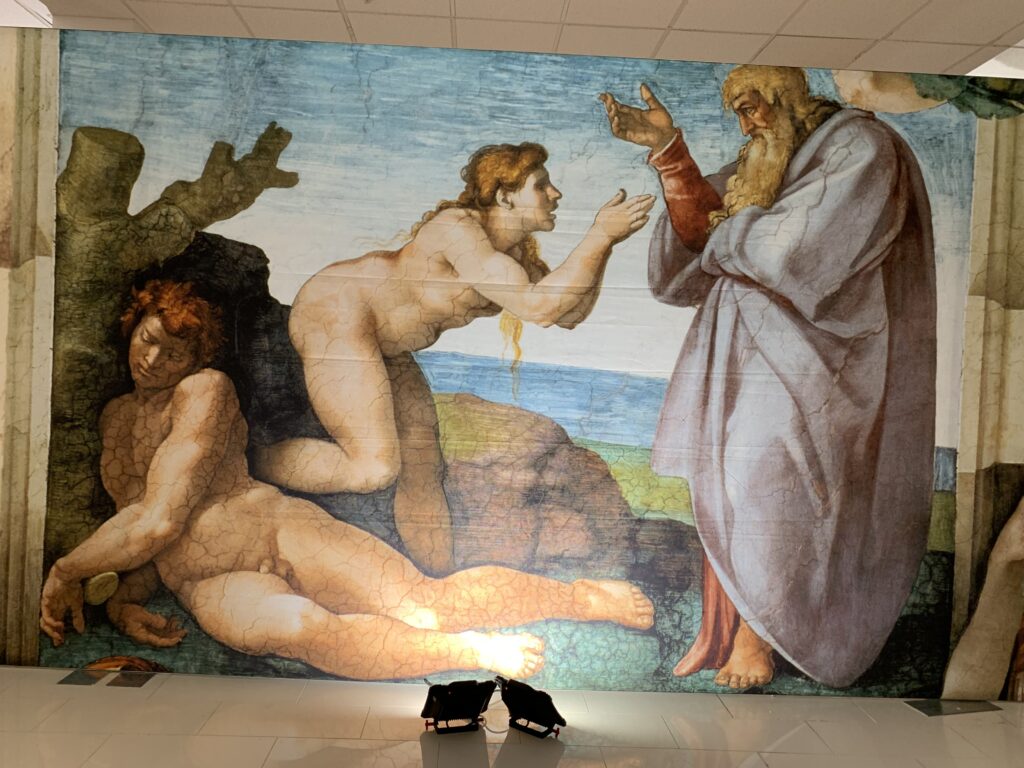

While less iconic, the Creation of Eve is no less evocative. Here we can see Eve literally emerging from Adam’s side; God is described as forming her from Adam’s rib. Eve and God seem to be having a verbal conversation, with Eve’s hands in a motion similar to prayer. Echoing Adam’s Creation, she too is depicted on the left and reaching towards God as he brings her into existence.

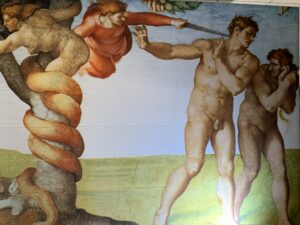

Temptation and Fall

Noah and the Flood

Old Testament Scenes

David was a popular figure in Italian Renaissance art, particularly in Florence where he was seen as the ultimate underdog hero, and a mascot or representative of how Florentines viewed themselves.

Here, we don’t see David with his sling; instead, this takes place after he’s struck Goliath down, and is just about to use the giant’s own sword to cut off his head. Michelangelo shows the scene right in the middle of the action and violence.

Here is yet another scene of decapitation, in this case showing the after-effects rather than the act.

Judith and her maidservant use their cunning to lure a vicious and cunning Assyrian general, Holofernes, into letting them have dinner with him. When the great enemy of the Israelites becomes intoxicated while trying to seduce her, Judith seizes the opportunity. Not only does she kill the Assyrian, but she also escapes the camp with Holofernes’ head. This scene has been a popular subject for many artists, including Carravaggio. Judith not only acts to help her people, but similarly to David, even strikes down an enemy when given the opportunity to strike.

Finally, in yet another violent triumph in the Old Testament, Michelangelo depicts the ending of the story of Esther. While there are not as many numerous female figures in the Old Testament compared to the men, Esther has an entire book to herself. She was an Israelite woman chosen to be the queen of a Persian king. Esther’s cousin and surrogate father, Mordecai, angers the king’s vizier Haman by refusing to bow to the man.

Finally, in yet another violent triumph in the Old Testament, Michelangelo depicts the ending of the story of Esther. While there are not as many numerous female figures in the Old Testament compared to the men, Esther has an entire book to herself. She was an Israelite woman chosen to be the queen of a Persian king. Esther’s cousin and surrogate father, Mordecai, angers the king’s vizier Haman by refusing to bow to the man.

Enraged, Haman plots to manipulate the king into giving an order to have all the Jews in the kingdom executed. When Esther hears news of this, she knows that it is up to her alone to save her cousin and her people. Despite being the king’s wife, she is still in danger herself; the last queen was deposed for insubordination to the king, so Esther is risking herself by making demands on her husband.

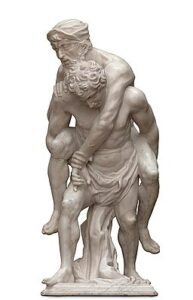

After having gained the king’s favor over several banquets, which Michelangelo shows on the upper left panel, Esther reveals Haman’s plot to kill her people, including Mordecai who had actually saved the king’s life from assassination. The king orders for Haman to be hung on the very gallows that the vizier had built to execute Mordecai. Here, Michelangelo doesn’t simply have Haman hung from a noose, though; he’s actually crucified, contorted in a complex twisting on an x-shaped cross. This reveals Michelangelo’s maturing and increased interest in pushing the human form in art to its limits, and complicated twisting poses which show off many angles and musculature, referred to as figura serpentinata or ‘serpentine form.’

The Last Judgement

In this complex depiction of The Last Judgement, an event referenced in Revelation and the culmination of the end of the world in the biblical Apocalypse, Michelangelo lets his imagination fill in this massive cast of subjects and events. The image itself is 180 meters squared, and depicts 390 figures, including saints, angels, demons, the souls of the holy, and the souls of the damned. The actual text of Revelation gives a simple description of a massively important event, the moment that, according to Christian theology, determines every person’s eternal fate. Michelangelo was commissioned to paint it in 1534, years after the ceiling had been finished.

4 Then I saw thrones, and those seated on them were given authority to judge. I also saw the souls of those who had been beheaded for their testimony to Jesus[a] and for the word of God. They had not worshiped the beast or its image and had not received its mark on their foreheads or their hands. They came to life and reigned with Christ a thousand years. 5 (The rest of the dead did not come to life until the thousand years were ended.) This is the first resurrection. 6 Blessed and holy are those who share in the first resurrection. Over these the second death has no power, but they will be priests of God and of Christ, and they will reign with him a thousand years. – Revelation 20:4-6

Here we see Michelangelo’s inspiration for the groupings of saints around Christ the Judge in the center of the image. Mary, the mother of Jesus, is by his right side, while a mass of martyrs surround the two. As is traditional in iconography and statues of saints, the martyrs are identifiable by their instruments of torture and execution.

One of the most grotesque images is that of St. Bartholomew on the right, who was flayed alive. He’s depicted holding his own skin, which is actually a self portrait of Michelangelo himself.

11 Then I saw a great white throne and the one who sat on it; the earth and the heaven fled from his presence, and no place was found for them. 12 And I saw the dead, great and small, standing before the throne, and books were opened. Also another book was opened, the book of life. And the dead were judged according to their works, as recorded in the books. 13 And the sea gave up the dead that were in it, Death and Hades gave up the dead that were in them, and all were judged according to what they had done. 14 Then Death and Hades were thrown into the lake of fire. This is the second death, the lake of fire; 15 and anyone whose name was not found written in the book of life was thrown into the lake of fire. -Revelation 20: 11-16

Jesus is shown separating the souls of the dead, and below they can be seen being led to the gates of hell to the right. There’s even a demon in a boat driving souls towards the mouth of Hell, a Classical reference to Charon the ferryman of souls to Hades in Greek mythology. Despite its deeply theological meaning, Michelangelo also includes sprinkles of mythological and Classical artworks.

Overall, this final image is the culmination of Michelangelo’s work, painted exquisitely and complexly even in his old age.

Seeing these images for myself in full scale and up close was a stunning experience. Looking at these pieces separately online or in books, or even in-person on the towering Sistine Chapel ceiling, is different from being close enough to touch the images. They’re massive (see the image below to see the scale of how large they are), complex, colorful, and sculptural. While they’re clearly artistic masterpieces, each one also holds layers of theology, mythological references, and even unfavorable depictions of people who got on Michelangelo’s nerves.

Sources

Michelangelo’s Sistine Chapel: The Exhibition Audio Tour Guide