The Green Knight Film Review

Part III: The Conclusion

By Noelle Weaver

A24’s The Green Knight is an adaptation of the classic medieval story Sir Gawain and the Green Knight. Most of the middle of the film, the rising action as Gawain wanders through the wilderness, is comprised of original scenes. Despite this straition from the original, the film sets Gawain back on a more familiar path when he comes across a castle in the middle of the wilderness right before Christmas. The people within are no less mysterious; a lord and lady, and an unnamed and unmentioned blindfolded old woman are Gawain’s only companions. Despite beng the only people he’s come across who haven’t immediately tried to rob him or turn out to be headless ghosts, Gawain is clearly exhausted and wary of his strange hosts.

Despite this, his time in the castle is the first time we see him in civilized society since he set out from the walls of Camelot. The lord and lady recognize Gawain, and already know about his quest to face the Green Knight. Even stranger, the lady looks exactly like his lover the prostitute Ethel; they’re played by the same actress. Once again the film leaves us to question if what we’re seeing is real, or a distorted reality shaped by what Gawain perceives. She gives him gifts, from a book to a portrait, and in an increasingly familiar action, takes Essel’s bell from Gawain in exchange. Even in this safe place, Gawain’s hosts want something from him in exchange for his company. The Lord proposes his game of exchange just as he does in the story; while he’s out hunting, Gawain can have whatever he gains in the woods. Meanwhile, Gawain will share whatever he’s given during the day.

The hosts and Gawain share a meal together, and their conversation turns to something that both readers of the originals and the film audience must be wondering about; why is the titular figure, the ominous knight, green?

The Lady offers an answer in a chilling Shakespearean monologue; green is the color of nature and of rot. As hard as men try to build over and stamp nature out, rot and growth will reclaim everything in the end. Nature is chaotic and unyielding, and no matter how much men demand and take from it, nature will always have the last laugh. It will take from men in return, whether they cut down a tree or lop off a head. Gawain’s experiences in the magical and cruel wilderness outside Camelot certainly support her assertions about the wild and exacting nature of the Green Knight.

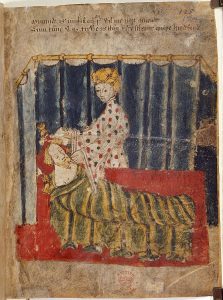

source: British Library CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Things come to a head in the castle as the lady makes an advance on the vulnerable Gawain in his bed chamber, just as in the story. There’s no exchange of wits here, though; the Lady knows what she wants, and she knows what Gawain wants, and she’s willing to use it against him. It’s disturbing as she promises the enchanted green sash once again to Gawain, the gift of his mother, forcing him into a sexual encounter in echange. Unlike in the story, Gawain gives into both temptations, taking the sash and indulging the Lady in infidelity against Gawain’s host. Gawain’s true consent in this situation is dubious at best, a disturbing reflection of his unwilling participation in all the exchanges he’s been forced into through out the story.

Gawain, like the audience, is horrified at this turn in his friendly relationship with both the Lord and the Lady and flees immediately after. He doesn’t stay in the house for three days until Christmas Day, and when he encounters the Lord he’s done with all of the tricks and games, as well as the offer of friendship; “I don’t want your games, or your gifts, or your kindness.”

It’s almost as if Gawain has finally realized that this cruel world, both in the wild and Camelot’s civility and honor, is built on a corrupted sense of exchange. The knight commits great acts to represent his kingdom and in exchange people sing songs of his deeds, even if the price is his own head. Challenges of character lie around every corner, waiting to jump Gawain. But in refusing this, Gawain is also rejecting the better angels of society, like the lord’s kindness and supporting friendship. This decision hurls Gawain on his trajectory to the Green Chapel, and foreshadows his decisions in the finale.

Gawain regains his fox companion for the final leg of his journey. The man who guides Gawain to the Green Chapel offers Gawain an out in the original story, promising he wouldn’t tell anyone if Gawain runs away and doesn’t face the Green Knight. In this version, the fox himself speaks, the offer of a friend and a final warning. He tells Gawain that he should turn back, and that he’ll find no mercy in the Green Chapel; the Green Knight is even more wild than the fox itself, and if he knew what was coming he’d be wise and leave. Gawain refuses the fox’s offer, swinging his axe at it to scare it away.

The nature of the fox is another thing left ambiguous to the audience; is the fox trying to trick Gawain, or is his advice to Gawain sound? Was it always a magical thing of its own, or is it a messenger for Morgan le Fey? The fox is the third animal that Lord Bertilak hunts in the original story, and serves as a parallel to Gawain who is being ‘hunted’ by the lady. Both are wily, but ultimately caught by their pursuer in the end. The fox at least serves as an inner voice to Gawain’s temptation to flee, similar to Essel’s urgings to Gawain to save his own neck and not die for a superficial sense of honor. Despite his two closest companions through the film both telling him not to go, Gawain presses on to the chapel likely more out of stubbornness than braveness.

Gawain goes to the Green Chapel alone to face the Green Knight. In a surprising twist, Gawain does what he’s been advised to do by the fox; when the Green Knight raises his axe, Gawain leaves behind both his honor and his doom and goes home. But what follows is no happy ending. The sequence of Gawain succeeding King Arthur, taking Essel’s son from her, marrying for politics and not for love, losing his son, and facing the fall of Camelot and his final doom plays out in horrifying fashion, with the dailogue-less scenes letting the visuals and acting tell the story. Through it all, Gawain wears the green sash; it’s his saving grace, but also what keeps him separate and distant from all others. His decision to save his own neck over living a life of honor leaves him cold and closed off. Just as King Gawain’s head falls off, we realize that this is once again us seeing what’s going through Gawain’s mind; he’s never left Green Chapel. Like his vision of himself lying dead as a skeleton, St. Winifred’s talking skull, and the giants, we’ve seen things through the eyes of Gawain. Instead of his life flashing before his eyes, Gawain has imagined his life if he keeps the girdle and refuses to accept honor and goodness into his life. Either way, he’ll die alone.

In a shocking act, Gawain does what the original story’s Gawain cannot; he takes off the girdle, accepting his death. The Green Knight pats Gawain’s face, repeating King Arthur’s earlier gesture, and we’re left to wonder if Gawain dies there in the Green Chapel or not.

This was not a loose adaptation written by someone who glanced at the barebones plot of Sir Gawain and the Green Knight and decided to do whatever they wanted to and threw it at the audience, like a lot of film adaptations of literature. Instead, director and writer David Lowery took what made Sir Gawain great and deconstructed the character and each test and encounter for a modern audience, both making it fit the hero’s journey structure and also challenging the tropes and conceptions around the link between plot development and character development. It answered the question of why Gawain didn’t just walk away from the Green Knight’s axe in the original, and more than that, it features an underdog and a ‘hero’ who lacks heroic qualities, yet in the end does what the perfect Sir Gawain can’t in the original; this Gawain passes the Green Knight’s test and removes the green girdle. This Gawain understands that he will meet death now with honor, or later without it, and the first is actually preferable. After two and a half hours of failing the tests thrown at him, Gawain finally makes the right decision in the very end. His character arc is the inverse of the original; Gawain the perfect knight navigates his challenges well, but in the end takes the green girdle and keeps it with him for his challenge. The film’s Gawain fails every test, but lets go of the girdle in the end and accepts an honorable death.

The Green Knight is not a film for everyone. It’s haunting, with visuals both beautiful and terrible at different points, and an incredible medieval-inspired soundtrack to add to the effect of each scene. The illuminated letters announcing each of the trials Gawain will face serve as an interesting structure to the film. It’s disturbing and upsetting, and keeps you on the edge of your seat with suspense. Some of what the audience sees is from Gawain’s eyes, some of it may be an actual acid trip, and some of it is just the magic of Camelot and the world of the Green Knight. The film takes you on a gripping journey both through the wilderness of Camelot and inside Gawain’s own head. It questions a narrative structure, The Hero’s Journey, we’ve long accepted as a part of the human conscience and natural structure of storytelling and asks whether or not someone is actually changed by a quest. Does seeking greatness make a person magically better than before? Why risk your life in the name of honor? Good stories make you ask questions about yourself and the world, and The Green Knight certainly does.