Who are the Daughters of Leda?

The Women behind the Myths

By Noelle Weaver

This past weekend, OWU’s drama group put on a stunning production of Madeline Sayets’s Daughters of Leda. The struggles and hurt of the characters genuinely brought me to tears, and they were painted well enough that you didn’t need to know all of their stories by heart to appreciate what they’re going through.

Even for those who are fans of Greek mythology, whether you enjoyed the Percy Jackson series or are into the Classics, may have difficulty tracking who all the different characters are. The play used characters from Ovid’s Metamorphosis, The Iliad, The Odysea, The Oresteia plays, and Sophocles’ Electra to portray one family, descended from Leda the matriarch. It also depicts Persephone and Hades and the three Fates, more popular characters in mythology. For those of who have never heard of Elektra, or need a refresher on Clytemnestra’s vengeance on Agamemnon, here’s an overview of the characters featured in Daughters of Leda.

The Daughters of Leda

The titular Leda is featured in her story Leda and the Swan, recorded by Ovid in his Metamorphosis. As is often the case, Zeus sets eyes on a beautiful mortal, the princess Leda. Despite it being her wedding day, he does whatever he has to to be with her, and in this case he transforms into a swan and comes to her in bird form. (If this seems weird, he transformed into a bird to woo Hera his wife, and in another he turned his mortal lover into a cow to hide her from Hera) Leda has two eggs, which give birth to her twins Helen and Clytemnestra- one the daughter of Zeus, the other the daughter of her mortal husband- and a much more familiar character emerges.

Helen of Troy, the most beautiful woman on the planet, is the daughter of Leda and Zeus. Helen, with “the face that launched a thousand ships.” Her lesser known twin is Clytemnestra. The two sisters go on to marry brothers, King Menelaus and King Agamemnon. These two are primarily featured in The Iliad. Before the events of the Trojan War portrayed in this famous epic, Helen leaves her husband Menelaus and goes to Troy with Paris. Whether this is of her own free will, or Paris kidnapping her, varies on the story and the interpretation, a concept that the drama plays with. Eventually the Trojans lose the war and are all killed, Troy is ravaged, and Helen is brought back with Menelaus to live the rest of her life in Mycanae.

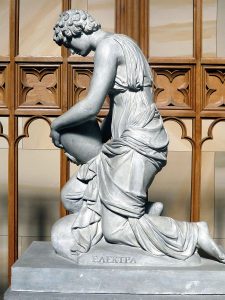

Meanwhile, Agamemnon leaves to support his brother Menelaus in getting Helen back. He has many children with Clytemnestra, the twin of Helen and his wife; their daughters Iphigenia, Elektra, and Chrysothemis appear in Daughters of Leda. In order to have success in the Trojan War, Agamemnon lures his daughter Iphigenia to come with him with the promise to marry her to Achilles; instead, he sacrifices her to appease the gods.

Unsurprisingly, Clytemnestra is a little angry with her husband for killing their daughter. When he comes home from the Trojan War ten years later, she and her new lover murder Agamemnon, as portrayed is Aeschylus’s Agamemnon. It’s interesting that both sisters cheat on the brothers Menelaus and Agamemnon, and both affairs end in bloodshed. Clytemnestra’s children Orestes and Electra are horrified, and in the next play of the Oresteia trilogy, they retaliate by killing their mother to avenge their father.

The seventh daughter of Leda, as the characters joke themselves, is much less known. I had to look her up after the play; it turns out that Chrysothemis, the sister of Electra and Iphigenia, lived a much less eventful life in myth and plays. She appears in Sophocles’ play on Electra and Orestes’s revenge on Clytemnestra, Electra. Chrysothemis does not partake in the murder of her mother, feeling that as a woman she’s powerless to do anything about the wrongdoings against her father. Electra proves her wrong by helping in the plot with her brother Orestes.

It’s no surprise that when The Daughters of Leda introduce these three generations that have experienced so much turmoil and bloodshed, the women aren’t all living tranquilly together in the underworld.

Persephone

The story of Hades and Persephone is a little more familiar and less spread out across epics and short myths. Persphone, daughter of Demeter the goddess of the harvest, is kidnapped by Hades. While in the underworld, the young and innocent Persphone eats pomegranate seeds offered to her by her host. When her mother Demeter arrives to save her, she realizes that it’s too late; Persephone has bound herself to the underworld by eating the seeds.

Famously, Persephone spends half the year with her mother during the spring and summer months. The other half of the year Persephone stays with her husband Hades in the underworld, which makes the harvest goddess Demeter let winter come and everything die with her grief. Persephone is a fascinating character in her duality, both a spring goddess and the queen of the underworld at once, and the play depicts her as much more than a submissive and innocent flower.

The Fates

One Fate weaves the threads that make up mortal lives, one measures it’s length, and the third snips the thread when the person’s life has come to an end. Quite appropriately, these three are named Spin, Measure, and Cut in Sayet’s play. They’re portrayed as three weaving women in mythology. The Moirai are surprisingly powerful, and at times even Zeus can’t argue with their authority. In the play Daughters of Leda, they’re portrayed as working for Hades, which makes sense since they dictate when mortals will die and come to his realm the underworld. In the play, they’re also shown as spinning the stories of the people through their own slants, as well as dictating the length of their lives. They’re storytellers, weaving the lives of mortals and shaping them to their will.

Daughters of Leda brought together the women in a family that was ravaged by fate, war, and vengeance. Seeing the twins Clytemnestra and Helen argue, Helen wondering what Leda thought of her leaving Menelaus for Paris, Leda’s anguish over her assault and the pain her family has endured, and the strife between Clytemnestra and her daughter/murderer Electra is heart wrenching, and a wonderful exploration of what it would actually be like to be a Greek heroine thrown about by the winds of fate. Even destiny is personified in The Fates, exploring the question of free will, and how the actions of someone will be interpreted by history. The depth and psychology of these female characters struggling with forces larger than themselves is so fascinating when you consider that they were written in a time when women were little more than property is, and their battle with their own agency becomes much more interesting in this context. Helen shows that women can make their own choices on who they want to be with (although their may be consequences), Clytemnestra shows the strength of a mother’s love, Electra proves that when you see injustice you can act even if you’re a woman, and Persephone proves that even in the worst circumstances you can choose to be a queen.

2 Comments

Comments are closed.