For some of us, finding our interests and what we want to do with our lives comes naturally. Dancers may talk about how as young children they watched performances for hours, and scientists may explain how they had always had a fascination with observing the natural world. But others end up finding their calling because they don’t like how German sounds—that’s how OWU’s own Dr. McOsker turned to Classics.

Dr. McOsker is one of the professors in the Classics department. You may have seen him around academic side, walking to and from his office in Slocum. One interesting piece of trivia about Dr. McOsker is that he is an OWU alum, having majored in Classics while he was a student here. But his journey to Classics is somewhat unexpected.

Slocum Hall is certainly majestic, and impresses anyone who approaches it. The stained glass and the Harry Potter-esque study room makes one feel that they have stepped back in time to OWU’s original founding in 1842. The large tables have been scratched into over the years, forever bearing people’s names and symbols of Greek Life. The stairs lead you to a balcony, where you can overlook the study room with ancient looking manuscripts. It is here where the Classics department offices are located.

As I made my way to Dr. McOsker’s office, I wonder how he would respond to me asking what got him into the Classics. I figured he would tell me about reading Greek mythology as a child, or maybe say that as a student he went to an archeological dig that piqued his interest. Much to my surprise, he answered in a matter-of-fact tone: “When I was in 7th grade, I had to start taking a foreign language. I did not like how German sounded, and I did not like the French teacher, and everyone was going to take Spanish. Latin was my only option.” A classic example of stumbling into your life’s calling. From there, McOsker stuck with Latin through high school, and by the time he was a junior, he had taken five years. “By that time I’d gotten reasonably good at it, and we had started to read actual Latin literature which I enjoyed a lot!”

From high school, McOsker went on to complete his undergraduate degree right here at Ohio Wesleyan. Again, the idea of a Classics major was not exactly a fulfillment of a life-long dream. “I tested straight into upper level Latin and basically thought that I might as well be a Classics major since I was already about half way done with it,” he said with a laugh. However, he did not stop at Latin. In Classics, a great emphasis is also placed on Ancient Greek. Many of the world’s most famous and important works from the ancient world are in Ancient Greek as well as Latin, so in his first year in college, McOsker started taking Ancient Greek as well. At that time he only had intentions of double majoring, and possibly pursuing a career in business. But, that was not to be. Throughout his time as an undergrad, he did not take an interest in his business classes the same way he did with Classics.

From high school, McOsker went on to complete his undergraduate degree right here at Ohio Wesleyan. Again, the idea of a Classics major was not exactly a fulfillment of a life-long dream. “I tested straight into upper level Latin and basically thought that I might as well be a Classics major since I was already about half way done with it,” he said with a laugh. However, he did not stop at Latin. In Classics, a great emphasis is also placed on Ancient Greek. Many of the world’s most famous and important works from the ancient world are in Ancient Greek as well as Latin, so in his first year in college, McOsker started taking Ancient Greek as well. At that time he only had intentions of double majoring, and possibly pursuing a career in business. But, that was not to be. Throughout his time as an undergrad, he did not take an interest in his business classes the same way he did with Classics.

However, having an interest in something is different than taking that interest all the way to making a career out of it, especially when being a Classics professor requires getting a PhD and writing a dissertation. And, once again, McOsker surprised me with what he had to say next. “I hated writing,” he said with a laugh, “like, loathed it!” He went on to explain that, because he hated writing, he wasn’t initially interested in becoming a professor. “The moment for me,” he explained, “was when I was in a Homer class my junior year and, for some reason, the professor left a term paper off the syllabus. It turns out it was an accident, but the class assumed that there would not be a final paper. However, there was something in the Iliad that caught my attention, and I began research.” He went on to say that the professor encouraged him to write a paper on this topic, and that this paper is what eventually got him honors in the class and into graduate school.

At first, it did not seem that he would elaborate on what this mysterious topic was. I asked for more details, dying to know the topic that got him into graduate school. He went on to explain that in the beginning of the Iliad, there is a scene where Achilles and Agamemnon get into a verbal fight. During the course of the fight, Achilles called Agamemnon a “man-eater,” or “devourer of the people.” This is what piqued Dr. McOsker’s interest. “I was struck by that… does Achilles mean that Agamemnon was literally a cannibal, or what? What’s going on here, exactly?” McOsker had read about the Bronze Age Greek civilizations, and he knew that there were tablets in Pylos dating from the day Pylos was sacked. An inscription on the tablets read something along the lines of, “The enemy is at our gates. Quick, dedicate a bull and a man to Zeus and a woman and a cow to Hera.” McOsker explained that “dedication” meant a sacrifice. “So what did it mean to sacrifice a man and a woman?” He told me that Greek sacrifices were normally eaten by the community. Did this mean that the community ate the man and the woman? Did this subtle insult by Achilles have a deep history in Greek culture?

“Turns out, I was totally and wildly off-course!” McOsker said with a laugh. The paper ended up having more to do with what the words meant as an insult. The idea is that if you are eating people, then you are not acting like a human being, but more like an animal. McOsker explained that this is in line with the other insults Achilles hurls at Agamemnon–“You have the heart of a deer,” “you have the face of a dog,” and so on–describing him as a cowardly, scavenging animal. “So,” MsOsker continued, “it had nothing to do with sacrifice or cannibalism. But I learned a lot about sacrifice, ritual, and cannibalism, just because it was very interesting to read about.” The argument was wrong, but the topic was right. Or, in other words, Dr. McOsker became a professor because he had a thing for cannibalism.

After our discussion of his origin story, I was curious to know more about McOsker’s current views on classical languages. Which language did he prefer, Ancient Greek or Latin? Once again, he surprised me. “Latin is like a first love, but at a certain point I was having more fun reading Greek authors than Roman ones. And now my scholarly work is on Greek.” There are different types of Ancient Greek. Like most classics students, McOsker first learned Attic Greek, which gives you the ability to read authors such as Plato, Aristotle, and Euripides. Homer’s Greek is different enough that McOsker had to learn the grammical rules for it, and now he studies many varieties of Greek.

McOsker lamented the fact that modern students of Ancient Greek are probably badly mispronouncing the language. “I know, I just know that we are mispronouncing Ancient Greek,” he said with some frustration. Ancient Greek has a pitch accent, so McOsker believes that it must have a sing-song quality, like Chinese or Swedish. Long and short vowels were originally more important than stressed accents, until eventually stressed accents replaced pitch. “I try to imagine hearing it, but I am not sure at all that I hear it well.” Greek also has longer words with a “flowing, harmonious quality.” But then McOsker immediately juxtaposes this image with a sturdier image. “With its cases, participles, and subordinate clauses, Greek, paradoxically, has an architectural quality.” He describes it as using a map that, when well thought-out, can be read straight through.

McOsker’s answer made me wonder why Latin seems to be the more popular language. High schools offer Latin classes, but I almost never hear about Ancient Greek. McOsker explained to me that students in the English-speaking world were traditionally taught Latin first because it was closer to the English language. The alphabet is the same and it appears less intimidating. Ancient Greek, on the other hand, has a different alphabet and sometimes different pronunciations of shared letters. In addition, coming out of medieval Europe was the tradition of reading and writing in Latin. With the exception of Greece, the rest of Europe came out of the Latin tradition. However, in Greece, the high schools teach Ancient Greek. “This way, the students are forced to enjoy Homer in his original language. Poor souls!” McOsker jokes.

It was when we were on the topic of language that I spring the question that Classicists hate the most: What is the value in learning a dead language? Did he see its importance in historical terms, aesthetic terms, or utilitarian terms? His answer was all of the above. He explained that it takes different skills to study a non-spoken language. For a living language, the emphasis is less on getting everything perfect, and more on just being understood. Once the communication is there, then the finer points of the language can be mastered. And if you study a language for a few years and go to a country where that language is spoken and master it that way. And if native speakers don’t understand something you say, they can always ask you for clarification. In a dead language, all this is impossible. It is on the person to make sure they are precise in their usage. Ironically, this is one of the things that makes studying a dead language rewarding–it’s like a private conversation you’re having with your favorite authors, and that requires a special kind of discipline. Though one might not be able to hold a casual conversation with a roommate who is also studying the language, the disciplined dialogue that goes on with the author is just as fruitful.

Of course, there are more straightforwardly pleasurable reasons for learning a dead language. “You always lose stuff in translation,” McCosker explained. In languages, things as simple as vowel changes, accent, and spelling can completely change the meaning of a word, and evoking the style of a certain authors can be difficult, as the English language is incapable of recreating certain effects this from Ancient Latin or Greek texts. “A translation gets you halfway, but there is a lot of artistry that you cannot appreciate unless you can read it in their native language.” He mentioned wanting to do a translation of some of Pindar’s works, which he describes as extravagant, filled with outrageous metaphors and compound words. English typically “flattens” his poems, but McOsker hopes to translate them literally, and keep the original words.

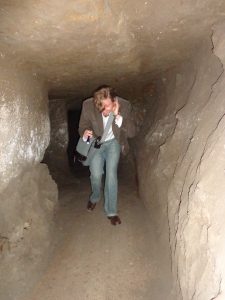

Before parting, I asked him about some of the benefits of being a Classicist. His answer was: travel! “Become a classicist and see the world!” In high school, McOsker’s Latin class took a joint trip with the Spanish students to Spain and Italy for a week. Later, as an undergraduate, he worked on an archeological dig in Israel. As a grad student, he chaperoned an undergraduate trip to Rome. And, later on, his research led him to get money from his Ph.D. program to go to Paris and attend conferences in Holland and Greece, and he got a fellowship to live in Naples for two years while conducting research.That way, he could see Europe and go to more conferences in Greece, Germany, and Poland. You see, Classics is a small field, making it very international in orientation. For his research, McOsker often finds himself emailing colleagues in many countries. He said that Naples will always hold a special place in his heart, because that is where his main research is, and Delphi in particular, because that is where he visited his first archaeological dig. “It is pretty spectacular,” he marveled.

As our interview drew to a close, we reflected on how OWU’s small class sizes probably also had an influence on his decision to pursue Classics. He was encouraged and mentored by his professors to pursue his interests, and so he tries to do the same for his own students. “I find that very valuable and rewarding.” When I mentioned the value of independent studies, McOsker added, “I am offering Hittite next semester, so if you know anyone wants to take a Bronze Age language…” Who knows, if you sign up you may become an accidental classicist yourself!