The AMRS program has recently added a new course to its curriculum: AMRS 100.1: “Thrice-Told Tales.” This course delves into the stories that humans have been telling for millennia. It was created by Dr. Zackariah Long. I asked him some questions about the course to get more specifics.

How did you come up with the idea for this course?

A few years back the Ancient, Medieval, and Renaissance Studies program created its first-ever course with an AMRS prefix, “History of the Book.” That course was designed as a common experience for majors from all three AMRS tracks to come together to learn about a topic important to all of their fields, and I really liked that idea. However, “History of the Book” is an upper-level course, which assumes a certain degree of commitment on the part of students. That got me to thinking about what a ground-level AMRS course might look like. Could I come up with a course that helped students understand what AMRS was all about?

Of course, I’m a literature professor, so naturally I started playing around with course concepts that involved literature written across the three AMRS periods. That’s when the idea of “Thrice-Told Tales” occurred to me. Now “Twice-Told Tales” is actually a very common college course—I think there was a “Twice-Told Tales” class at my undergraduate institution! But some quick Google searches revealed that courses that brought together three versions of a tale are much more uncommon, and I found that appealing. Plus, it just seemed right: one of the things that makes AMRS unique is that it encompasses the three eras, whereas most premodern and early modern interdisciplinary programs only cover two. So I liked the idea of teaching a course that reflected what was distinctive about AMRS.

Why did you choose the tales that you did?

Well, first and most obviously, they needed to be tales for which there were three different versions, one in each of the three AMRS eras. That was actually a bit trickier than I anticipated: it was easy to find examples of tales told twice, but harder to find three. (Maybe that’s why “Twice-Told Tales” is the more popular option!) I also really wanted to pick texts that were foundational–works that either had a profound impact on the literature of their own or of subsequent periods, or that distilled something fundamental about their moment in history, even if they didn’t prove influential in the future. Third, I wanted to assign tales of different types and on different subjects, so that we weren’t just reading the same kinds of things over and over again. Finally, as much as possible, I didn’t want to repeat too much of what students might read in my other classes or the classes of my AMRS colleagues should they decide to continue their studies in the program.

It turns out that finding tales that fit all four of those criteria was quite challenging. In retrospect, that should have been obvious–if there aren’t lots of thrice-told tales, period, then there aren’t going to be many of them that are foundational; and if works are foundational, then my colleagues will naturally want to teach them too. However, in the end, I felt like I was able to achieve a balance among my criteria and come up with a set of nine texts–three groups of three (Dante would be pleased)–that encompassed a range of literary kinds and subjects.

It turns out that finding tales that fit all four of those criteria was quite challenging. In retrospect, that should have been obvious–if there aren’t lots of thrice-told tales, period, then there aren’t going to be many of them that are foundational; and if works are foundational, then my colleagues will naturally want to teach them too. However, in the end, I felt like I was able to achieve a balance among my criteria and come up with a set of nine texts–three groups of three (Dante would be pleased)–that encompassed a range of literary kinds and subjects.

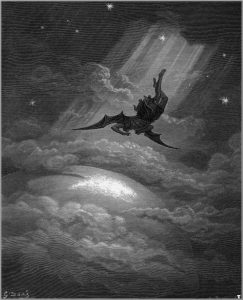

Unit 1 is on heroism; our three texts are The Iliad, Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, and Don Quixote. Those tales are obviously not linked together by a single story, but by a kind of story–the story of a hero’s journey or adventure. In The Iliad we are introduced to one version of the classical epic hero in Achilles; in Sir Gawain, we see how heroism is reinterpreted in a chivalric context; and in Don Quixote we see how the chivalric code is satirized and deconstructed in the modern world. Unit 2 is on marriage, and for that unit we do focus on a particular story–the myth of Demeter and Persephone–as retold in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, Chaucer’s The Merchant’s Tale, and Shakespeare’s The Winter’s Tale. Here our subject is the deeply unsettling connection between marriage and violence in the literary tradition. Finally, Unit 3 is on theodicy, which is the project of ‘justifying the ways of God to man.’ The focus here is on the story of the fall and redemption of humanity as told in the Christian Bible, the Wakefield mystery play cycle, and Paradise Lost.

Through these selections, I feel like I was able to tag a lot of the thematic epicenters of the Western European literary tradition. Plus, if students go on to take other courses in early or premodern literature, they’ll have quite the background to draw from!

Some works you assign in their entirety and others only in part. Why?

This question pains me because I hate to assign selections from works and, in my other classes, I make a point of not doing it. However, in a nutshell, the answer is space. The Iliad, Don Quixote, The Bible, Paradise Lost–you could teach standalone classes on any one of these texts (and in some cases I have), but you could never assign all of them in their entirety in a single class. It would just be too much, especially for a lower-level course. But I felt that such texts came the closest to achieving my goals, especially the goal of introducing students to works of literature that could be foundational to their future studies should they continue to take AMRS classes. In the end, I decided that I cared more about that vision than adhering to my usual rule of never assigning selections. But I won’t lie, it was hard.

What was the most challenging part of teaching this new course?

Without a doubt, the prep work involved. When you are teaching works written over the course of millennia, you by definition can’t be an expert in all of them, even if you have read them many times or have studied them in connection with texts or topics in which you are expert. Take, for example, The Iliad–I’ve actually done a fair bit of reading on the epic tradition in general and have studied the reception of Homer in the English Renaissance in particular. But that’s not Homer’s Iliad–that’s Chapman’s Iliad or Milton’s Iliad, and so on. Teaching Homer in his original context is a different matter entirely. So there’s a lot of preparation. I don’t mind that work–in fact, it’s one of the things I love most about teaching new classes–but it is very time-consuming and can get exhausting. I often end up staying up late, until 4 or 5 in the morning, prepping for class, which I’m frankly getting a bit old for and is a little self-defeating, since then I’m tired for class. (I feel I can relate to my students for this reason.)

I honestly don’t know how much of this preparation comes across to students. I tend not to come in and dump a bunch of information on them–10 to 15 minutes of lecture at a time, max–because this course is really about grappling with these wonderful and challenging texts and unpacking the intertextual connections among them. So a lot of the prep never really shows up in lecture or discussion. But it’s a necessary part of the process for me. To be satisfied with myself, I need to have as good a handle on these things as I can, and of course I want to try to avoid saying anything dumb. In literary studies, there are lots of ways to be right; it’s being flat-out wrong that I try to avoid.

Is there a reason why we just can’t stop telling certain tales?

I think the tales we keep telling are those that are working through something–stories that grapple with intractable questions, probe fundamental human impulses and conflicts, or express deep-seated cultural fantasies and anxieties. We tell stories about these things because narrative is the fundamental human strategy for trying to make sense of the world–to try to explain why things happened the way they did, or why certain things keep happening over and over again. If we can tell a coherent story about something, then we feel like we’ve got it figured out. But certain human desires, dilemmas, or situations are just too big–they repeatedly frustrate our attempts to make sense of them. Now, you’d think that would discourage us from telling stories about them, but in fact it’s just the opposite. We find others’ attempts unsatisfactory, so we have to try for ourselves. There is an irony here. Because the dilemmas that provoke these kinds of stories are usually insoluable, the stories we tell about them often end up being unsuccessful, at least in rational terms. But the process of trying to capture them in narrative’s net is pleasurable, and the promise of doing so irresistible. So we keep trying, and we find meaning in that struggle, in that pleasure. It reveals us to ourselves.

— Interview by Amanda Hays