Nestled in the 5th Arrondissement of Paris, France and constructed on what remains of a Roman thermal bath house, one will find the Musée de Cluny—or the National Museum of the Middle Ages—a less frequented but still impressive museum. Among its extensive collection of medieval and ancient pieces is a collection of tapestries known as The Lady and the Unicorn, famous for being one of the greatest surviving artworks handed down to us from the Middle Ages.

Created in the French millefleur (thousand flower) style of tapestry work, the collection of six pieces were discovered in 1841 by Prosper Mérimée, an important writer in the French Romantic school. Though they had suffered damage due to their poor storage conditions in Boussac Castle, the tapestries managed to catch the eye of various littérateurs and other public figures, capturing the imagination of viewers; eventually they were turned over to the Thermes de Cluny in Paris. From that time to the present, delicate conservation and care has managed to restore the tapestries to their former glory.

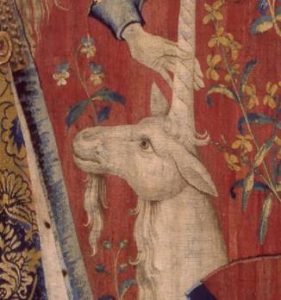

As the name suggests, each one of the tapestries depicts a lady of noble bearing accompanied by a unicorn on her left and a lion on her right. Though the exact meaning of the tapestries has been lost, the prevailing theory is that they offer a commentary on love and its relationship to the senses associated with human experience. The museum seems to support this interpretation, arranging the tapestries in a circular manner beginning with Touch, in which the the lady is depicted with one hand on the unicorn’s horn while the lion gazes on, and progressing through Taste, Smell, Hearing, Sight, and ending with the sixth and most unique piece in the collection– the À Mon Seul Désir. Translated, the phrase means “with my unique desire” and is suggestive of a mysterious and powerful sixth sense. Wider and crafted in a style diverging from the rest, the sixth tapestry depicts the lady standing in front of a tent that states the title of the tapestry. To the noblewoman’s right is her maid- servant, bearing an open chest into which the noblewoman is placing her necklace. The unicorn and the lion continue to flank the lady on either side. Though this piece of the tapestry has elicited a number of interpretations, including the aforementioned “sixth sense of love,” more recent scholarly work has culled a meaning from the tapestries that is perhaps more interesting.

This interpretation has taken the French phrase scrawled onto the tent combined with the woman placing her valuable necklace in (or retrieving it from) the box as a commentary on the unique human capability to desire material possessions while the other five senses are ones that we share with animals, whether real or mythological. Arguably, the necklace could also be symbolic of any other traits unique to humans, such as faith in the divine, love, or the ability to reason. Proponents of this interpretation cite the fact that in the other five tapestries, which represent the senses derived from and shared with nature, either the unicorn or the lion are somehow engaged in the sensory experience, whereas in the sixth tapestry both merely watch from afar as the two women interact with the necklace in the safety of their blue tent—a juxtaposition against the dominant shades of green in the other five pieces. The sudden appearance of the tent and it’s difference in shading seem to suggest that the tent acts as a barrier between the two women and the outside world of nature and myth. Following this interpretation to its logical conclusion, the tapestries seem to suggest a recurring motif which has resounded through art, literature, religion, and philosophy: Humans live alongside the combined realm of nature and myth, and have, arguably, progressed out of that realm and into a state that is uniquely ours. It remains a curious aspect of our fate to stride the line between these two worlds, never entirely at home in one or the other.